“Miss Morrow stood on her podium. “The End of the World is the myth of the twentieth century. It is present in every piece of art created. Take a note!” she commanded. “Black pens.” She waited until the shuffle subsided.

“We have no optimism.” In fact, Miss Morrow did not really like much ofher century’s art, or its thinking. Still, they had to study it. “Even the Eastern religions with their ideas ofreincarnation provide only fatalism. We in Western society fear that we are facing an explosive, utter annihilation of the world, brought about by nuclear war perhaps, or the destruction of the environment.” She paused for the students to catch up to her. “Or the destruction of the environment.

Because we in the West do not believe in rebirth, this end of the world we anticipate will be final.”

The pens scratched over paper.

“Indent,” said Miss Morrow. “Underline. Cassie, you need a ruler, you can’t underline with the edge of a file folder!”

Cassie scrabbled through her pencil case.

Miss Morrow went on. “Since the beginning of the century the visual arts, literature and even music have altered so totally that we can call this change a destruction of the language of art. It appears at times that painters want to erase the entire history of their art. In fact they wish to revert to chaos.”

Miss Morrow looked down at the students in the front rows.

“You remember Chaos? It’s what Milton wrote about. Chaos. Give me a definition.”

“I can’t find my ruler,” said Cassie.

“Then you are excused to go and get one.”

Cassie stood up. She knocked her binder off the desktop. The rings sprang open and pages broke out onto the floor. Some groaned. Others laughed. Cassie stood looking down in dismay.

“Well, go!” snapped Miss Morrow. Her eyes widened. She might have rolled them had her ethics not strictly curtailed her from mocking her students. “Cassie, you would try the patience of Job!”

Cassie went, hanging her head. Half-giggling from nerves.

“Give me a definition of Chaos,” Miss Morrow said again, in her wake.

“The inside of Cassie’s locker?” piped Maureen.

Miss Morrow looked horrified. “I do believe that is the pot calling the kettle!” It was one thing for her to comment, another for the students to comment on each other. Vida raised her hand. “What is it now?”

“I don’t have my book.”

Miss Morrow heaved a sigh. “Go then,” she said. And gave up getting a serious answer to her question.

She resumed her lecture, looking straight toward the back wall of the studio. “Yet is it truly all darkness where we are going? Is this wiping out not in itselfa new idea, a creative act? And that in itself is hopeful. It shows that our artists can be roused to answer back, to fight back, to rebuild a coherent world.”

There were days when Francesca believed this. Days when the certain existence of the darkness ahead seemed to demand a response. But she saw that she would lose what audience she had left if she continued in this vein. She made the graceful segue, as if premeditated, the favourite tool of the trade of teaching. “The beloved Master understood this.” She bid the class turn to their loose-leaf binders full of colour Xeroxes of art book reproductions of famous paintings, faithfully copied by Amelia and distributed to the students early in the year. Many a class was spent simply gazing at pictures while Miss Morrow lectured. Here was comfort. Here was-

“-G. F. Watts. Perhaps the greatest painter of his time! Imagine how lucky I have been to have been drawn into his aura by my mother! Although I never met the man, I have learned everything I know from him. Consider his portraits of William Morris, of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, of Tennyson, copies of which you should have in your binders. These are my links, direct links to the past, to that coherent world of which I spoke.

“Turn to the pages of Watts paintings, please. His audacious canvases of allegorical subjects captivated the people of his time. He bridged the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, moving forward but at the same time bringing us back once again as the artists of the Renaissance brought the public back, to the earliest classical forms. His Orpheus and Eurydice. His Echo. His Aristides and the Shepherd.

“Often have I thought of Aristides over the years. A great citizen of Athens who was ostracized by his fellow citizens. And why? Because of jealousy. ‘I am tired of always hearing him called the Just,’ they said, and cast the fatal disc to have him thrown outside the walls. “

Somehow, today, Watts was not so comforting.

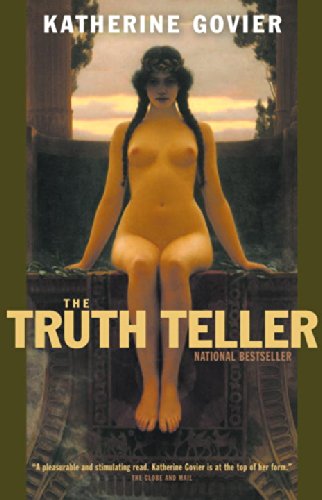

“Oh, and Psyche. Turn your pages. You have it there. So beautiful. So sad. You know the story, girls and boys, of Psyche? How Cupid falls in love with her and visits her at night? She knows she must not look at him, but she is overcome with curiosity, and she can’t resist. Holding the lamp over his face, she lets fall a drop of oil. He wakes. Psyche is caught in the act. Therefore, Cupid is lost to her. Do you understand? To see all is to lose all. So teaches the myth. And I believe it.

“Turn the page again. His Minotaur. Oh, especially his Minotaur. This is a painting! It prefigures all the disintegration and chaos that is to come. Watch how the monster is portrayed, wistfully leaning on the wall, watching for the ships to come bearing the Athenian youths and maidens given in tribute for him to consume in his maze. You see the art of reduction, or symbolic representation, how less is more: why would we want to see the carnage itself, why would we need to see the blood of sacrifice? Better to dread its coming, and to gaze upon the half-human visage of the monster.” – Katherine Govier, The truth teller